Emotion research has a communication conundrum

In 2025, the words we use to describe emotions matter, but their definitions are controversial. Here, I unpack the different positions in this space and the rationales behind them—and I invite 13 experts to chime in.

I remember a faculty meeting during my first year as an assistant professor in a psychology department, now 15 years ago, when a colleague proposed that we search for a faculty member in “affective science.” I was puzzled by what that meant, but afraid to ask for fear of looking foolish.

There are nontrivial reasons that some emotion researchers insist on calling brain functions that others label an “emotion” an “affective state” instead, and likewise, what others call a “mood” a “temporally extended affective state.” At the same time, these unfamiliar terms impede communication with non-experts, including members of the public. With the value of U.S. science being called into question and a growing need for scientists to communicate their research more clearly, this matters. Conflicting definitions of “emotion” also lead to confusion.

Controversy around how to characterize emotions dates back to ancient times; Aristotle preferred the passive term pathos to describe them. Today, researchers still don’t agree. Following the recent publication of the paper “Conserved brain-wide emergence of emotional response from sensory experience in humans and mice,” one researcher expressed concerns about the current state of the field to the press, explaining, “The underlying problem is that scientists still don’t agree on how to define an emotion.”

What’s behind all this disagreement? And what can be done to broaden communication about emotion research with the outside world? Here, I unpack the different positions in this space and the rationales behind them. I also invite several experts to chime in on the question, “What should be done about the communication conundrum in emotion research?”

What makes studying emotion so challenging?

Understanding the debate around terms in emotion research requires appreciating why emotions are more challenging to study than other brain functions. To investigate memory, for example, researchers often design a memory test for which there are ground-truth correct and incorrect answers to the questions posed. In contrast, emotion is a subjective experience for which there is no ground truth—no one but you really knows how happy, anxious, scared or disgusted you are. This subjectivity makes emotions much more difficult to measure than other brain functions, especially in animals, because we cannot ask them how they feel.

The most extensively used measure of emotions is applied by simply asking people questions about their feelings, such as: “On a scale from 1 to 5, how upset are you?”. However, measures of subjective experience are limited to humans who can communicate and cannot be applied to nonhuman animals or young children. A second type of emotion measure probes biological reactions triggered by emotions, including facial expressions or galvanic skin responses; often, however, these responses do not map cleanly onto subjective reports. Other versions of physiological measures seek to quantify how emotions are reflected in dynamic patterns of brain activity (or their proxies, such as fMRI results). A final way to measure emotion is to induce an emotion and measure how it changes a person’s behavior on a well-defined task, such as a paradigm for risky decision-making. These different ways of measuring emotions set the stage for debates about what these measures should be called, centered around the evidence they provide.

To understand debates about emotion-related terms, it’s helpful to begin with textbook definitions of what those terms mean. According to one popular undergraduate psychology textbook, an emotion is an immediate, specific negative or positive response to environmental events or internal thoughts. The term is used interchangeably with affect. An emotion has three components: physiological changes (such as a galvanic skin response or pupil dilation), a behavioral response (such as a facial expression or running away) and a feeling based on cognitive appraisal of the situation and interpretation of body states. The word feeling is reserved for the subjective experience of emotion, which differs from the emotion itself. In contrast, moods are diffuse, long-lasting emotional states that do not have an identifiable trigger. Getting cut off in traffic can make a person angry (emotion), but for no apparent reason, a person can be irritable (mood). Definitions like these can help separate these concepts when studying them experimentally.

Though that backdrop might make this all sound simple and straightforward, hidden behind it is a lot of complexity. For instance, mental health researchers define mood differently, in ways that focus on what triggers its changes. In fact, so much controversy exists around terms in emotion research that more than 170 authors were inspired to unite to find the root causes of these definitional conundrums. They determined these to be differences in underlying goals and assumptions across theories of emotion, and they integrated those into a principled and cohesive framework called “The Human Affectome“—a terrific step. Still, controversy about what to call emotion-related phenomena remains. Here, I’ll describe two flavors of naming conventions in turn.

Debates about conscious experience and whether “emotion” can be studied in animals

The rationale behind the textbook definition of emotion described above follows from the idea that events can trigger “emotions” that, when sufficiently strong, can be experienced consciously as “feelings” like happiness or fear. The corollary is that emotions can exist subconsciously, an assertion that is supported by some evidence. In one study, for example, viewing emotional facial expressions subconsciously (briefly, followed by a perceptual mask) affected behavior—the amount of a pleasant beverage consumed.

According to this framework, because we cannot probe subjective experience in nonhuman animals, we can study emotions in animals—guided by well-defined criteria for what constitutes an emotion (described in more detail below)—but not feelings. One advantage of this framework is that the motivation behind studies of emotion is reflected in its description using words that anyone can relate to: analogous to the various terms for “memory” (such as “recollection memory”), emotions are described with terms such as “happiness,” “fear” and “mood.”

Some researchers, however, maintain that the term “emotion” and its flavors should be reserved for cases in which conscious experience is evident. They argue that because we cannot probe the subjective experience of animals, animals, by this definition, cannot have emotions but instead have “affective states.” One rationale behind this position is to prevent the downstream consequences that may follow from misattributing emotion-related behavior as emotional awareness. As some researchers argue, the subcortical neural circuits that support fear-related freezing behavior may be distinct from the cortical circuits that support the conscious experience of fear. As such, labeling those subcortical circuits “fear circuits” and targeting them for therapeutic interventions to relieve conditions such as post-traumatic stress disorder may be misguided.

By the same logic, the longer-lasting states called “moods” cannot be studied in animals, but researchers can study “temporally extended affective states.” One motivation behind this position is the desire to clarify what’s what, to ensure that no one gets confused, including the researchers themselves. Moreover, these terms are used in the service of an important end-goal: explaining what we consciously experience. Reserving the term “emotion” for such conscious experiences ensures that researchers keep their eye on that prize.

Notably, calls to reserve “emotion” for cases in which there is direct evidence of conscious awareness (unique to humans) set a higher bar for using the word “emotion” than researchers typically do for using terms for other brain functions. For instance, evidence for “memory” can come in all manner of forms, including how much longer a nonverbal human infant or a monkey will look at an image that they’ve never seen before versus one they have (a measure of “recognition memory”). Concerns about this higher bar for defining emotion include that it impedes communication with the public and that it disincentivizes nonhuman animal research, where arguably some of the biggest discoveries are being made. After all, you would have to be quite a neuroscience aficionado to be curious about a paper with “temporally extended affective state” (rather than “mood”) in its title.

Debates about the criteria for what counts as an “emotion”

A second axis of the debate around what constitutes an emotion is the criteria for inclusion, even for humans (with whom subjective reports are available). Researchers generally agree that not all feelings are emotional: for instance, you can feel tired or hungry, but those are not typically considered emotions. The general idea is that emotions are triggered by external events that are real, remembered or imagined: for instance, fear is triggered by seeing a tiger. In contrast, tiredness and hunger are triggered by events that are internal to the body. Pain is considered an edge case.

When focusing on what an external event triggers, how do you decide if it’s an emotion? Does an obnoxious puff of air to your eye that triggers an unpleasant experience count? Under one set of criteria, it does. These criteria include that the experience falls on one side of a good/bad divide (valence), it’s surprising (arousal), it extends beyond the time the air puff is present (persistence) and it triggers multiple behaviors, such as eye closing and tearing (generalization).

However, not all researchers agree with those criteria. Some prefer to call the experience that follows an air puff to the eye an “affective state” and assert that the term “emotion” should be reserved for situations that involve a cognitive interpretation of external events (such as seeing a tiger) and internal body states (such as flushed cheeks). The idea, in part, is that emotions are not just triggered by stimuli, but also depend on context—seeing a tiger safely confined to its enclosure at the zoo or on a television won’t trigger fear. That said, what exactly counts as “context” is not well defined. For instance, the negative emotional experience following an air puff to the eye is not immutable, but disappears following a medical intervention (ketamine administration)—does that count as context? Either way, it’s worth noting that including context as part of the definition raises a different bar to using the word “emotion” than researchers typically apply for other brain functions, such as “perception.” In particular, some forms of visual perception can also be contextual, yet we don’t say that a bright flash of light is not perceptual merely because it always triggers the percept “bright flash of light.”

Stepping back, many debates about defining emotions boil down to different theoretical ideas about what drives them. One example is the tension between basic emotion theory and the theory of constructed emotions. In basic emotion theory, emotions (fear, disgust and so on) exist at their core as discrete categories designed to solve adaptive problems: for example, disgust follows from the fact that eating poisonous things is harmful. Proponents of basic emotion theory advocate for definitions of emotions that align with those discrete categories. In comparison, the theory of constructed emotion aligns with ideas about predictive processing. Inherent in this theory is the notion that any sensory signal can have more than one emotional meaning, depending on context. Proponents of constructed emotion theory highlight this as one of the components of emotion that must be considered when studying it. Categories are thought to be constructed ad hoc in a specific time and place (i.e., a specific context) for a particular function. In this view, the evolutionary adaptation is the ability to construct categories in the service of metabolic efficiency to control action, not the identity of the specific categories themselves (which are acquired via learning). In this view, there is not a single category for “anger,” but a distribution of spatiotemporal anger categories.

An important dimension of this conversation is thus the degree to which definitions of the phenomena of interest can and should be made independent of theories about how emotions come to be. Separation between the two has worked for some scientific problems (as when the thermometer developed in the 17th century, enabling the measurements required to converge on thermodynamics in the 19th century), but for emotion, progress may require intertwined definitions and theories, because it’s a different and more complex problem.

What do researchers think?

To better understand what researchers think, I asked various people in the field: “What should be done about the communication conundrum in emotion research to maximize communication with non-experts, minimize confusion both within and outside the field, and inspire progress?” Here’s what they had to say.

Responses

The modern English word “emotion” first appeared only about a hundred years ago; different languages have many words and concepts available to describe emotions; there is little agreement among the many different theories of emotion; and even experts seem stumped when asked for a definition. All this would make you think that “affective science” is largely a cultural invention rather than a science for discovering something in nature. I strongly disagree with that conclusion.

Instead, I think that a science of emotion will become one of the most vibrant, and most important, disciplines—in good part because of the diverse approaches. The words and concepts available for emotions of course predate modern science, but in this they are no different from other concepts, like “mind” or “thinking.” Or, for that matter, “space” and “time.” The trick is to come up with scientifically useful concepts that are, on the one hand, sufficiently continuous with our folk psychology so that we have not changed the topic, yet, on the other hand, sufficiently revised so that science can use them. My own view (comments welcome) is that, in the case of emotions, this will require distinguishing emotions as functional states (e.g., being in a state of fear) both from conscious experiences of them (e.g., feeling afraid) as well as from concepts for them (e.g., talking and thinking about fear). We have made these distinctions with topics like vision or memory, and doing so will make it possible to study emotions in animals and robots without needing to solve hard problems about consciousness.

I am a physician scientist who performs translational research to develop improved treatments for obsessive-compulsive disorder and anxiety. My perspective on the “communication conundrum” is therefore steadfastly anchored in trying to maximize the likelihood that our findings in the lab will actually translate into new therapeutic interventions for people. I view clear and precise communication of what is being studied when investigating emotion and mood—both of which are heavily impacted in psychiatric disorders—as essential to performing rigorous and replicable research that creates clarity, rather than confusion, in the field. Standardized definitions and comprehensive methods descriptions (including environmental context) will facilitate this.

We are currently at an unprecedented juncture in neuroscience and psychiatry, with line of sight to the development of precision treatments matched to the biology of individual patients. This promise is highlighted in the description of Multi-Channel Psych, a $50-million Wellcome Leap program I built and directed over the past three years with the goal of doubling the number of people who respond to a treatment for their depression on the first try. To capitalize on our major investments in neuroscience research over the past 20 years and fulfill this promise, public buy-in is essential. I firmly believe it is possible to be accurate and precise in communication about discoveries, so as not to sow false hopes in patients desperate for breakthroughs, while still conveying excitement about their impact. We must prioritize communication training for scientists to ensure mutual understanding between researchers, patients and the general public.

Scientists have been debating the same questions about the nature of emotion for more than a century. Empirical evidence, no matter how sophisticated, is unable to resolve even the most basic issues.

The reason: The science of emotion is anchored in two distinct scientific paradigms, also called scientific traditions or academic ideologies. These two traditions differ in their foundational assumptions, concepts, methodologies, observations and inferences, as described here and here. Each tradition describes emotion-related phenomena using similar words, but they speak past each other, reflecting an important concept called incommensurability. Scientists from different traditions routinely misunderstand one another in the most fundamental ways or ignore one another to build consensus within their own tradition.

The result: The two traditions remain siloed, limiting the accumulation of useful scientific knowledge about emotion that is required to understand basic neurobiological mechanisms and harness them to devise interventions for emotion-related challenges that actually work in the real world.

The solution: Deal with this blind spot head on. Incommensurability is a concept from the philosophy of science. At the mention of philosophy, many scientists tune out. But don’t. Like it or not, if you are a scientist, then you are a practicing philosopher, even if you believe your scientific efforts are purely data driven. Some of the toughest and most intractable scientific debates, such as those in the science of emotion, are actually philosophical disagreements in disguise.

Emotion and pain are not neuronal “contents”; they’re psychological, linguistic labels—a sort-of subjective dimensionality reduction that compresses continuous, multiscale experience into communicable categories. Neurobiology fires in milliseconds, yet folk terms such as “fear” or “pain” splice together processes stretching from seconds to hours. When we go circuit-hunting in nonhuman models armed only with those words, we risk confusing the label with the neural activity codes.

Pain shows why temporal granularity matters. Within about 300 milliseconds, a pinprick is parsed into bodily site and mechanical qualities (sharp, dull). Hundreds of milliseconds later an affective, valence-laden appraisal surfaces, recruiting adaptive motivational behaviors for protection that can all be rapidly tuned up or down based on context. Yet clinical practice collapses this entire cascade into a single point on a 1–10 scale—an extreme compression that hides the dynamics we need to explain.

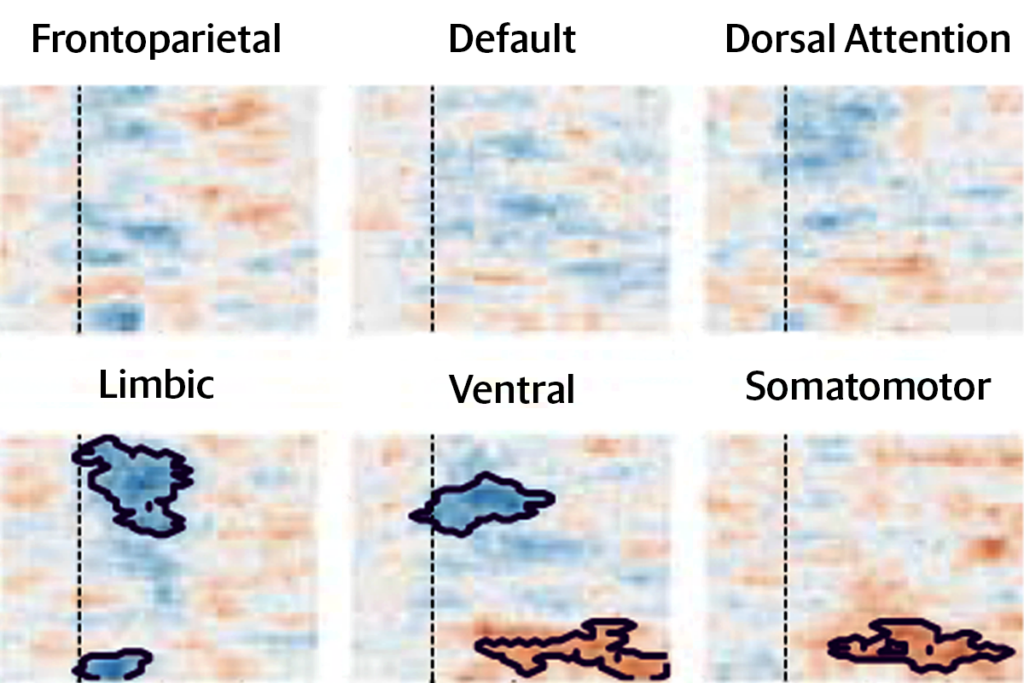

A recent cross-species eye-puff study sharpens the fix. Kauvar et al. mapped brain-wide activity in mice and neurosurgical patients, revealing a conserved two-phase motif: a 200-millisecond sensory broadcast followed about 700 milliseconds later by a slower, distributed affective state whose duration tracked self-reported discomfort.

The lesson is to build a tiered glossary grounded in mechanism: micro-states defined by precise neurophysiology, meso-states expressed as probabilistic motifs over seconds and macro-states aligning with the everyday psychological vocabulary that clinicians and patients already use. With active input from basic neuroscientists and emotion psychologists, maintaining this hierarchy as an open, regularly updated glossary would let researchers, clinicians and the public discuss emotion and pain clearly, without getting lost in semantics.

Good terminology can either advance or hinder scientific progress and shape public understanding. As scientists, we are drawn to conceptual frameworks that usefully constrain our predictions. As communicators, we favor language that strikes the right note, evoking intuitive understanding without oversimplifying. Both aims, I believe, are best served by a broad and inclusive definition of emotion—one compatible with evolutionary continuity of internal experience across species.

A key fault line in emotion research concerns the assumption that conscious emotional experiences (feelings) can be accessed only through verbal self-report, and thus only in humans. This assumption is worth reexamining. It takes a small, intuitive step to consider that nonverbal infants, other primates and other animals may have some privileged access to their own experiences. If we grant them a primitive capacity to inspect their own internal states and the behavioral vocabulary to report on them, the privileged status we afford verbal report becomes harder to justify. Holding onto that assumption constrains our ability to work on a unified and evolutionarily grounded account of emotion.

If a puff of air to the eye causes a persistent, negatively valenced internal state that generalizes across contexts, it seems uncontroversial to call that state an emotion. Our criteria may be axiomatic, and the relative weight of conscious access, appraisal or context remains debatable. But perhaps, to draw on the parable of the blind men and the elephant, theorists are simply inspecting different parts of the same elephant. Pending further evidence, why not assume that emotions are the whole elephant?

As in individualized medicine, in which treatment is tailored to each patient, communication about emotion should be adapted to the audience. The general public, even when interested in science, is more drawn to the relevance of our concepts to everyday life than to theoretical nuances and debates about definitions. For a lay audience, I describe emotions as dials that amplify the importance of certain signals in the brain and set an organism’s energy state to meet its behavioral agenda. Whether we call them emotions or affective states, cross-species comparisons must be part of the conversation. Precise measurements in animals are essential, not only to better understand the neural instantiation of affective states, but also to identify a putative shared core of what may be a unitary phenomenon expressed differently across species.

We should also avoid perpetuating ideas that stall progress. A persistent error is to equate emotional behavior with emotional (affective) states. We assume that if someone feels anger, they will behave angrily. Yet, detailed measurements show no one-to-one match. For example, aggression and predation may look similar but arise from different mental states. Such mismatches are even clearer when comparing brain circuits responsible for mental states to those driving observable behaviors. When we develop rigorous measurements for the right parameters, our concepts become clearer and easier to communicate.

Emotion and consciousness need each other. I first studied emotion in relation to consciousness in split-brain patients in the 1970s. I was fascinated with emotional consciousness but, because of the limitations of the methods for studying the human brain at the time, I chose to study emotional behavior in rats. I had no illusion about being able to understand emotional consciousness in animals, but I did believe that studies of emotional behavior in rats might be relevant to human emotional behavior, which I assumed was relevant to human emotional experience.

As time went by, I realized that something was wrong, as I describe here, here and here. It was assumed by many in the field that the best way to understand human emotions, such as fear, and their pathological consequences, such as anxiety, was to measure objective responses (freezing, fleeing, avoidance or increased heart rate) in animals. Even though such research had failed to find effective new treatments for emotional disorders, the quest continued because it was assumed that the pharmaceutical magic bullet was just waiting to be discovered. But, as the failures demonstrate, you cannot treat human mental problems with drugs that change animal behavior. People seek the help of therapists because they feel bad. The subjective emotional feelings of humans must also be treated (as I describe here, here and here), and for that to happen, an understanding of emotion in relation to human consciousness is required. As Nico Tinberg said in 1951, fear and other emotions can be known only by introspection, and when applied to other species, the terms are merely guesses about the possible nature of the animal’s subjective state. Unfortunately, consciousness researchers have been more interested in perception than emotion, and emotion researchers more in behavior than in subjective conscious experiences. Hopefully “a change is gonna come.”

The questions raised in this piece—which properties demarcate emotions from other phenomena (e.g., hunger, pain); what the ingredients of emotions are (i.e., constitutive explanations); what causal factors and mechanisms generate or undergird them (i.e., causal-mechanistic explanation); and how to measure emotions—are all relevant questions that have yielded a variety of answers in the field. Yet the mother of all questions—whether emotions are a fruitful scientific set at all—is often circumvented, including in this discussion. This fundamental question should not be treated as an afterthought, to be postponed until all other questions have been answered. Several of these other questions turn out to be deeply intertwined with that fundamental one. Here is how: Theorists start from a working definition, drawing provisional boundaries around the set of phenomena that lay people tend to call emotions (by listing properties or emotion types). Then they seek explanations for these phenomena, in the hope that these will provide a unique common ground for the phenomena and thereby set the boundaries for a scientific definition of emotion. If this process is successful, the set of emotions is vindicated; if not, it can be revised, split, turned into a “fuzzy set” or eliminated. Many scholars of emotion are “vindicators,” taking for granted that the set of emotions is a fruitful scientific set and that all that is left to do is justify this and discover where its boundaries lie. If one is willing to adopt a “skeptical” attitude, however, a different conclusion may lie ahead (see here, here, here and here).

In the context of mind-brain research, defining emotion is not productive because it suggests that we can carve out “emotion” as a separate mind process, as well as carving out “emotion” from the brain (e.g., “territories XYZ constitute the emotional brain”). With colleagues, I have argued against these possibilities here, among other publications.

Mental categories are often used in a dual fashion to denote both the problem (the phenomenon one aims to explain) and the solution (the mechanism proposed to provide the explanation). In this manner, mental terms are used in a circular fashion. For example, “emotional” processing and mechanisms are defined in terms of systems that are purported to be part of the emotional brain, such as the hypothalamus or the amygdala; conversely, a structure that plays an important role in “fear” is considered part of the emotional brain.

More forcefully, mental terms are frequently epistemically sterile. Evolutionary pressures have molded the nervous system to promote survival. Careful characterization of the vertebrate brain shows that its architecture supports an enormous amount of communication and integration of signals. The general neuroarchitecture supports a degree of “computational flexibility” that enables animals to cope successfully with complex and ever-changing environments. Thus, the vertebrate neuroarchitecture does not respect the boundaries of mental terms (“emotion,” “cognition,” “motivation” and so on).

In conclusion, progress requires developing new terms and ways of using language in more nuanced ways. “Emotion” is too broad a term to be of scientific value.

I would argue that we need to define these terms computationally—what computations do these representations encompass and enable? Then we can ask how to measure those computations. Key here is whether to prioritize verbal responses (“Are you hungry?”) or physical responses (gurgling stomach, changes in taste responses in gustatory brain structures, willingness to take costly actions to get food). I suspect that feeling hungry is computationally more an emotion than not, as it is context dependent, does not (necessarily) reflect one’s need for calories and has subjective and objective components. You can get hungry from seeing a picture of a pizza. Or even from imagining a pizza. Most human experiments prioritize verbal responses, whereas most nonhuman experiments prioritize physical responses, but everyone who has dealt with an overtired toddler vehemently denying that it is time for bed knows that one should not be prioritizing verbal responses. I think a lot of the problem is that we over-anthropomorphize humans.

Humans have a very successful folk psychology (likely evolutionarily important for a sociopolitical species!). In other fields, constructs either are completely new (“bits” in computer science) or have a long enough history that we have forgotten how poorly they align with lived experience and intuition (“momentum” in physics). This problem of using words with a lot of baggage—such as “memory,” “deliberation,” “imagination” and “regret”—has plagued neuroscience and psychology throughout its history. Defining them computationally can alleviate that and allow us to see how cognition really differs across species.

Different theoretical camps arrive at their constructs of emotion and other affective phenomena from different backgrounds, each with their own explanatory goals (e.g., identifying neural circuits versus characterizing variability) and their own assumptions about the phenomena being studied (what each one is, how it arises, how to measure it). Many of these theoretical differences cannot be settled empirically—because they involve the theory-laden aspects of designing experiments, selecting analyses and interpreting data. The definitional conundrum of emotion rests on this diversity of underlying theoretical frameworks. One potential avenue toward understanding how these differing theoretical assumptions relate to each other is to identify a principle of why emotions, or indeed affective phenomena at large, exist. Synthesizing decades of theory and research from various corners of the academic field, the Human Affectome is a framework that offers such an approach. Specifically, it converges on a set of nested teleological assumptions: Affective phenomena exist to ensure the organism’s viability, by executing operations, when enacting relevance, through entertaining abstraction. For this purpose, humans (and other organisms) have affective concerns—which address what is relevant and actionable in the environment on varying degrees of abstraction (e.g., food, danger, moral)—each characterized by affective features (valence and arousal). We can organize these phenomena as algorithms in relation to each other, such as physiological concerns (sensations), operational concerns (emotion), trajectory concerns (mood) or optimization concerns (well-being). Thus, the Human Affectome framework calls for an integrative rather than an adversarial endeavor to encourage an interconnected, rather than siloed, era of affective research.

I think we first need to acknowledge the wide rifts that exist between different camps of researchers over basic questions of what emotions are and what they are for. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy offers a helpful tripartite scheme: emotions as feelings or qualia, emotions as evaluations or appraisals, and emotions as motivated states or causes of behavior. The latter two have an especially dense history of butting heads, as exemplified by the ongoing conflict between Basic Emotions Theory (BET) and the Theory of Constructed Emotions (TCE), which has been elaborated across many publications over the past 20 years. TCE draws largely from the appraisal tradition, whereas BET draws from the motivational tradition, and some take these theories to have totally opposite ideas about the ontology of emotions and their role in the “mental economy.” However, I think many researchers are somewhat quick to put the cart before the horse when assuming the truth of one of these theories, whether in scientific discussions or in science vulgarization, perhaps because of their training or a natural tendency to think of humans as either primarily instinct-driven or primarily cognitive creatures. It might also be the centrality and familiarity of emotions in our mental lives that gives us that extra confidence. But in my opinion, the jury is still out on many of these foundational questions, and we should do our best to engage with them!

Emotions are by their nature vitally important to our health and wellbeing: They arise particularly from the events and situations that matter the most to us. But they are not well operationalized as constructs. The only widely accepted criterion for telling when an emotion is present is subjective: I am angry if I say I am angry. Of course, there are multiple indicators: My face may flush with blood, my fists ball up, my blood pressure rises. But these are not the emotion; they are only indicators that point to the possibility of emotion, as a finger points to the moon. An isolated brainstem surgically separated from the forebrain can, when stimulated electrically, trigger all of these signs—but we nonetheless cannot be sure that the brainstem is experiencing an emotion. Conversely, I may claim to be angry about an injustice, or even capital-I Injustice, even though I show none of those signs. Our lab’s work, along with that of many others, shows clearly that the different indicators of emotion—self-report, physiology and behavior—are not interchangeable and do not measure the same thing. Rather, they each result from activity in particular neural circuits, and each of these three is in fact a complex, multifaceted set of distinct processes. These different “channels” can become coordinated during an emotional episode but are nonetheless distinct.

People will inevitably use the word “emotion” to mean different things in different contexts, and I do not have a solution for that. In my work, we use “affect” to refer to feeling states that motivate behavior and learning and “emotion” to refer to feeling states that are more elaborated and differentiated. Emotion is a subset of affect. Feeling thirsty, tired, excited, in pain or just plain “good” are varieties of affect, but we usually do not call them “emotions” unless terminological precision is not a priority and we think the word “affect” will be confusing to an audience. Responses to air puffs, painful events and so forth may reasonably be called “affective,” because they influence motivated behavior but more rarely elicit emotions—unless I become angry at you for puffing air into my eye, or jealous of the person next to me who did not get similar treatment.

Recommended reading

The visual system’s lingering mystery: Connecting neural activity and perception

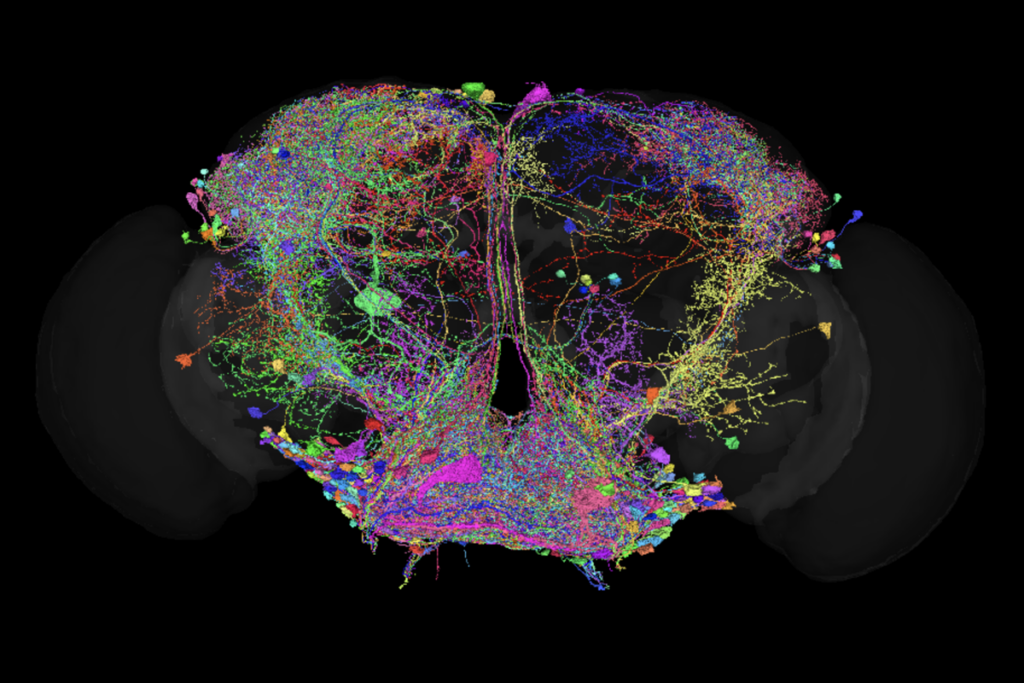

One year of FlyWire: How the resource is redefining Drosophila research

Beyond Newtonian causation in neuroscience: Embracing complex causality

Explore more from The Transmitter