MARRAKESH, MOROCCO—Imagine a neuroscientist in Brazil boosting their study’s power with data from Cameroon, or a Kenyan researcher validating a local result in a North American cohort. Currently, that could not happen: Differences in data-sharing laws, access to technology, and research ethics across countries pose obstacles to moving brain data across borders, or even getting them online in the first place.

But a new initiative seeks to address these barriers. The Brain Research International Data Governance & Exchange initiative, or BRIDGE, which is funded by the Wellcome Trust, is in its second year of a three-year project to establish a policy framework for storing, securing, accessing and working with neuroscience data internationally.

Last month in Marrakesh, Morocco, BRIDGE hosted a workshop with African neuroscientists during the annual meeting of the Society of Neuroscientists of Africa, along with a symposium in which they presented the information BRIDGE has collected so far.

The initiative’s global focus seeks to remedy a scientific problem: Most available brain data don’t represent the world population. For example, major online datasets, including the Human Connectome Project, the Cambridge Centre for Ageing and Neuroscience dataset and the UK Biobank, are drawn largely from people of European ancestry. People of African descent make up less than 5 percent of cohorts, on average, in brain disorder research, according to a 2020 review.

BRIDGE plans to change that by connecting data across Africa, South America, Europe and North America. In each of these regions, BRIDGE has started to assess the current data landscape through ambassadors in four domains: technology, ethics, law and people with lived experience of brain conditions. BRIDGE also gathers input through global and regional workshops involving neuroscientists as well as academics, clinicians, research and health organizations, and patient advocacy groups.

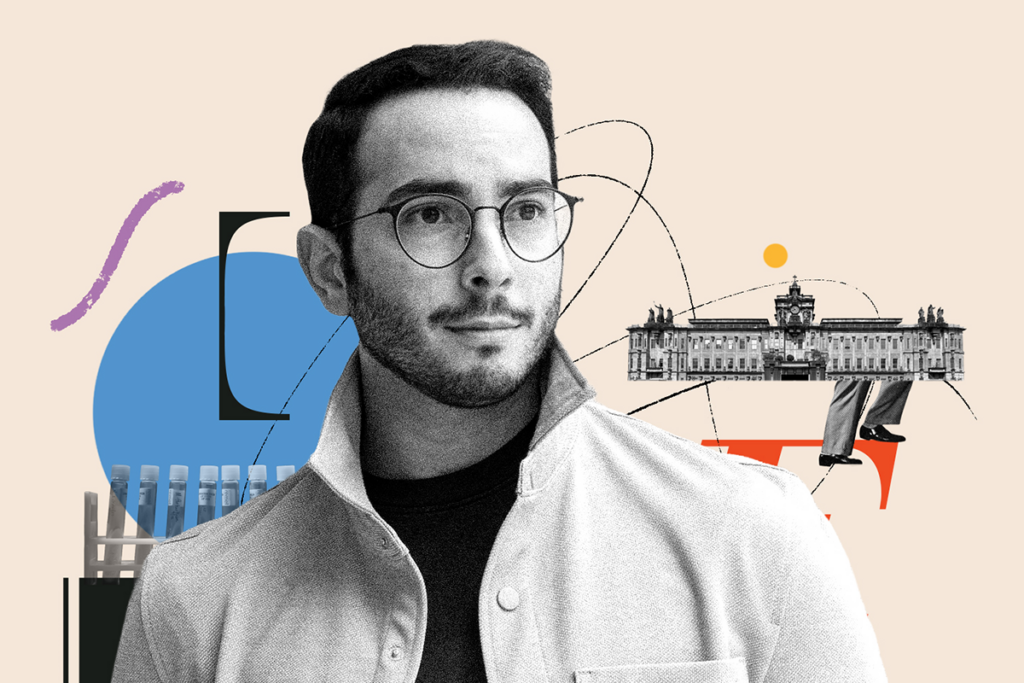

“The most important takeaway for BRIDGE is the diversity of understanding and approaches to data governance on the African continent,” says Amadi Ihunwo, a neuroscientist and one of BRIDGE’s co-investigators. This diversity is familiar to Ihunwo; he is from Nigeria, has worked in East Africa and is now based in South Africa, where he heads the School of Anatomical Sciences at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg. “This should discourage proposing unilateral templates to brain data generation storage, access and usage. BRIDGE would do well to highlight this and encourage the recognition of the unique approaches,” he says.

The Transmitter spoke with Ihunwo about the challenges and opportunities BRIDGE has encountered.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

The Transmitter: Why are data generated in Africa important to include in this initiative?

Amadi Ihunwo: There are 54 countries in Africa. That in itself shows the diversity on the continent. It’s necessary, especially in this age of looking at global and therapeutic interventions for mental health challenges, to recognize the diversity and heterogeneity of the dataset that can be acquired from Africa. Including data from Africa becomes virtually mandatory for advancing neuroscience.

However, not much data from the African region is available in a format so that others around the world can engage with it and also harmonize and compare it with global data. BRIDGE’s benefit to basic research is that empirical data will be generated and made available in an accessible format. In March of this year, members of the BRIDGE collaboration published the first MRI dataset from Nigeria, which they got by convincing individual diagnostic centers to provide this data.

The ultimate goal is a sustainable global coalition to make sure that there’s a robust, international data governance framework for international collaboration. No matter where you are, you will be able to access what we’re going to create through BRIDGE.

TT: How does BRIDGE plan to deal with regional concerns, such as data colonialism or participant consent being a community rather than an individual question in some African cultures?

AI: On the African continent, there is that communal aspect when you’re speaking about issues around mental health. These are sensitive areas. In the environment where we operate, the dimension of consent for the generation, storage and probable use of personal or brain data does vary significantly, even on the continent itself. And so if there are areas where there is communal consent, we’re saying they should be recognized. I think that is not something that many in the field are used to working with previously.

The awareness of data colonialism was drawn from the fact that before, you used to have data going out of the continent without involvement of researchers within the continent. And for BRIDGE, that needs to change. We want to see a situation where there is involvement of researchers from the beginning.

TT: Your wife, Uchenna Amadi-Ihunwo, a patient experience researcher and advocate, is BRIDGE’s ambassador to incorporate input from African people with brain conditions. Could you talk a bit about her work?

AI: The discussion in mental health research is heading toward recognizing people with lived experience, especially in terms of what tools to use, what direction to take and how to get their voices included from the beginning. Uchenna is the executive director of the Brain Wellness Initiative, a foundation I set up to work on brain research, brain data, training and funding on the African continent. That’s brought Uchenna in direct contact with families that needed to speak to somebody.

We hope that BRIDGE will be able to propose methodology drawing from the concerns, directions and suggestions that people with lived experience have expressed, especially when we’re discussing data from people with mental health challenges.

TT: One of the key challenges you presented in the symposium was the lack of funding for data-storage infrastructure. How is BRIDGE addressing that?

AI: BRIDGE does not have any dedicated funding for providing hardware infrastructure per se. But through existing projects that members are involved in, BRIDGE can train young African scientists in open-source tools that are critical in the data science arena. This is being facilitated through the African Brain Data Network’s African Brain Data Science Academy, which is led by one of our co-investigators, Damian Eke; and through Brainlife, a free open-source, secure and reproducible neuroscience-analysis platform based at the University of Texas at Austin and run by our principal investigator, Franco Pestilli.