New organoid atlas unveils four neurodevelopmental signatures

The comprehensive resource details data on microcephaly, polymicrogyria, epilepsy and intellectual disability from 352 people.

A biobank of more than 300 genetically diverse human stem cells has helped reveal the biological mechanisms underlying four neurodevelopmental conditions. Entries include the donors’ clinical details and data from brain imaging, histology, whole-exome sequencing and single-cell transcriptomics, highlighting both overlap and divergence in the phenotypes of genetically diverse conditions.

The resource is “second to none,” says Julien Muffat, a scientist at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto, who was not involved in this work. “The breadth of coverage across modalities is quite unique. It’s the sort of thing that the field needs.”

This biobank was initially part of a larger project that began about a decade ago, when the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine, a state-run stem cell and gene therapy agency, created a repository of human induced pluripotent stem cells, or iPSCs. As part of that intiative, study investigator Joseph Gleeson, professor of neuroscience at the University of California, San Diego and his colleagues obtained consent and collected samples from hundreds of people with any of four conditions, including two characterized by clear structural brain anomalies (specifically, microcephaly and polymicrogyria), as well as two without such differences (epilepsy and intellectual disability).

Taking those samples, the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine generated iPSC lines from 352 people in eight countries. Although the institute has since shut down its biobank, those lines are available for free through Gleeson’s lab. “If someone requests them, we’ll just send them at no cost,” Gleeson says. “Patients contributed to this effort, and we want to make sure that the community can benefit.” (The accompanying data are also publicly accessible via the UCSC Cell Browser and the U.S. National Institutes of Health’s database of Genotypes and Phenotypes.)

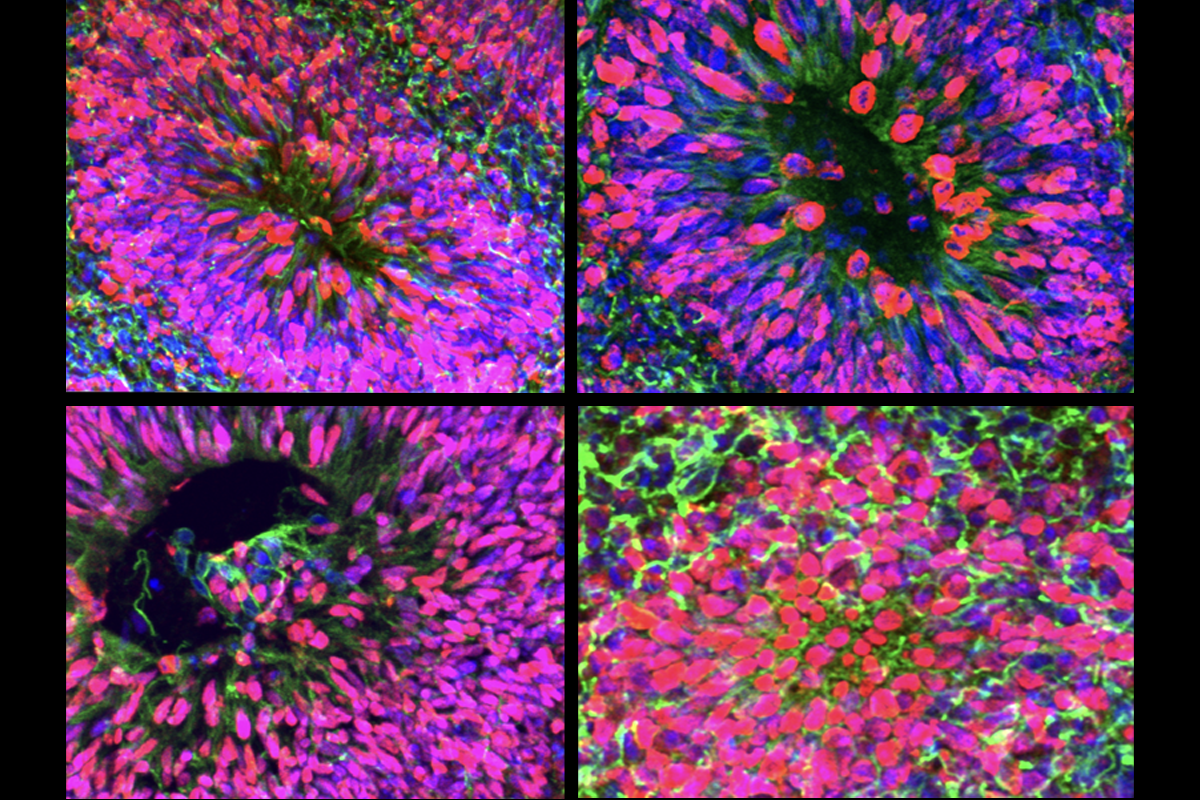

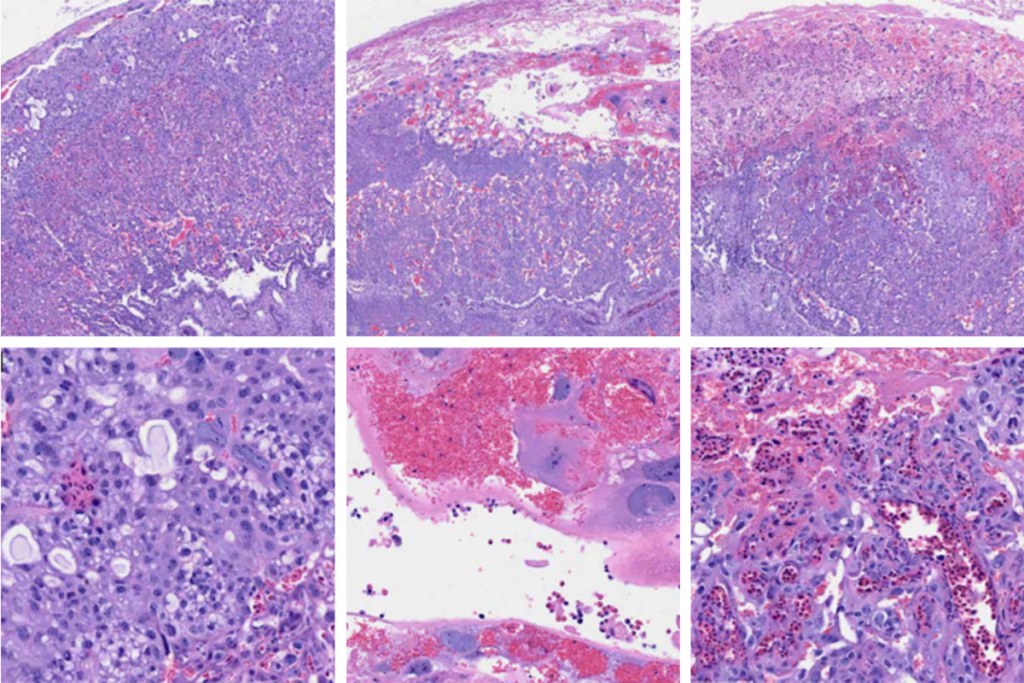

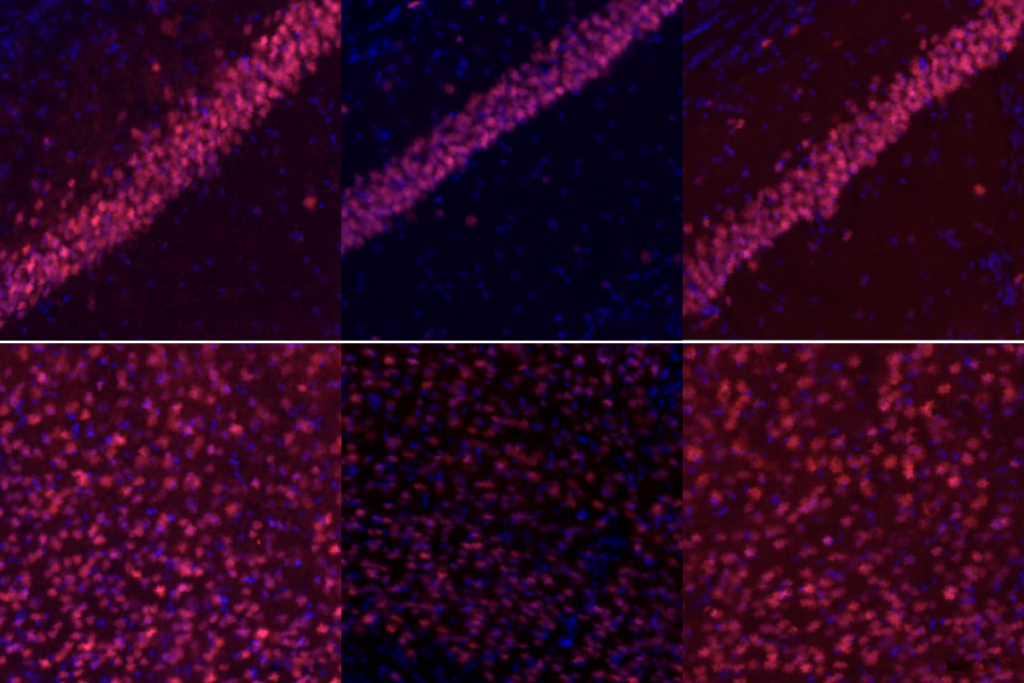

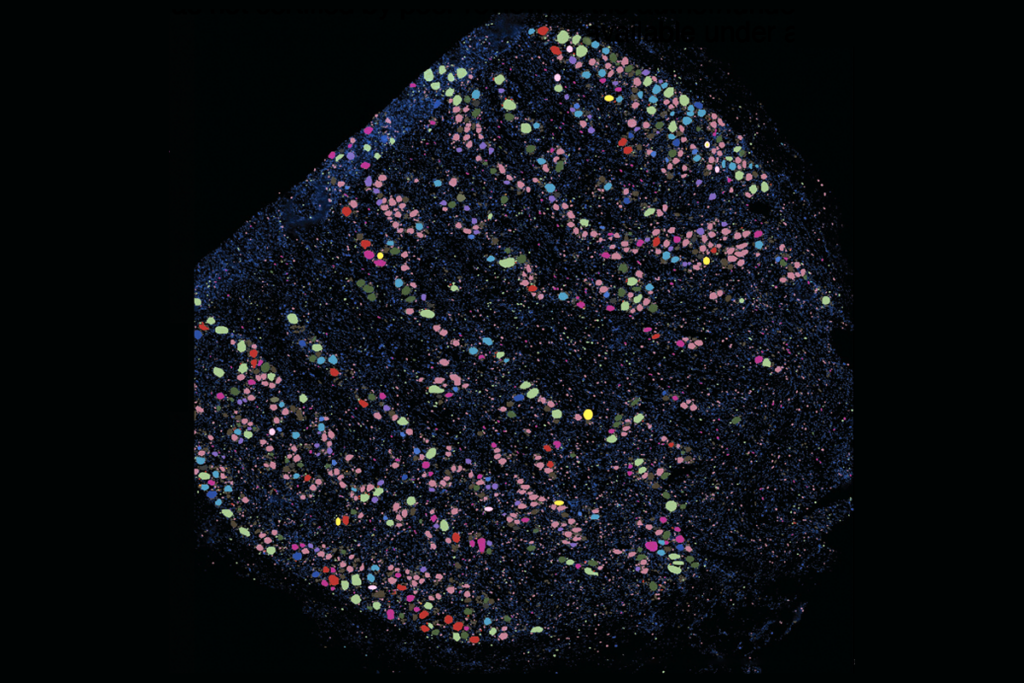

Using a subset of iPSCs from 35 participants (approximately half of whom had known causative genetic variants) and 10 unaffected controls, Gleeson and his colleagues created an “atlas” with more than 6,000 brain organoids. They then examined those organoids using histology and single-cell transcriptomics. The findings were published 3 November in Cell Stem Cell.

Together, the biobank and atlas provide scientists with a platform to probe disease mechanisms and validate therapeutic interventions, Gleeson says.

O

ne particularly surprising finding is that organoids from people with the same condition—despite different underlying genetic variants—have similar phenotypes, says study investigator Lu Wang, assistant professor of dentistry at the University of Southern California.For example, the organoids from people with microcephaly show a reduction in neurons and an increase in the number of cells expressing the protein transthyretin, which are found in the choroid plexus, a network of blood vessels in the brain. The organoids from people with epilepsy show an excess of astrocytes.

Identifying such condition-specific anomalies is important, “because in the future, doctors studying any patient can know that, if they made an organoid from them, they could more or less confirm the clinical diagnosis from the phenotype that’s derived from the cells of the patient,” Gleeson says. “That’s a complete game-changer.”

Muffat agrees, noting that patient-derived organoids could both help investigate the pathology of a condition and offer a way to identify and test new therapeutics. “I’m certainly one of the optimists that thinks that we’re going to have some of these [organoid] avatars rather soon,” Muffat says. “And large biobanks are instrumental for that.”

Gleeson says that their work could also offer a foundation or reference point for future biobanks focused on other conditions. “We’re just scratching the surface of what’s possible.”

Recommended reading

Post-infection immune conflict alters fetal development in some male mice

In-vivo base editing in a mouse model of autism, and more

Explore more from The Transmitter

Constellation of studies charts brain development, offers ‘dramatic revision’

‘Unprecedented’ dorsal root ganglion atlas captures 22 types of human sensory neurons