Cell ‘antennae’ link autism, congenital heart disease

Variants in genes tied to both conditions derail the formation of cilia, the tiny hair-like structure found on almost every cell in the body, a new study finds.

Cilia, hairlike structures on the surface of cells, may be involved in congenital heart disease (CHD) and autism, according to a new study published last month in the journal Development. Variants in genes tied to both conditions impair cilia formation in cells, the research shows.

The finding could explain why people with CHD are about twice as likely to be diagnosed with autism.

“This study is really exciting and interesting because it gives us more insight” into this overlap, says Shiaulou Yuan, assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, who studies cilia in heart development but was not involved in the work. “It seems like cilia is a common unifying mechanism.”

These antenna-like structures are found on almost every cell, “so it’s not surprising” that cilia-related genes “could affect multiple organ systems,” Yuan adds.

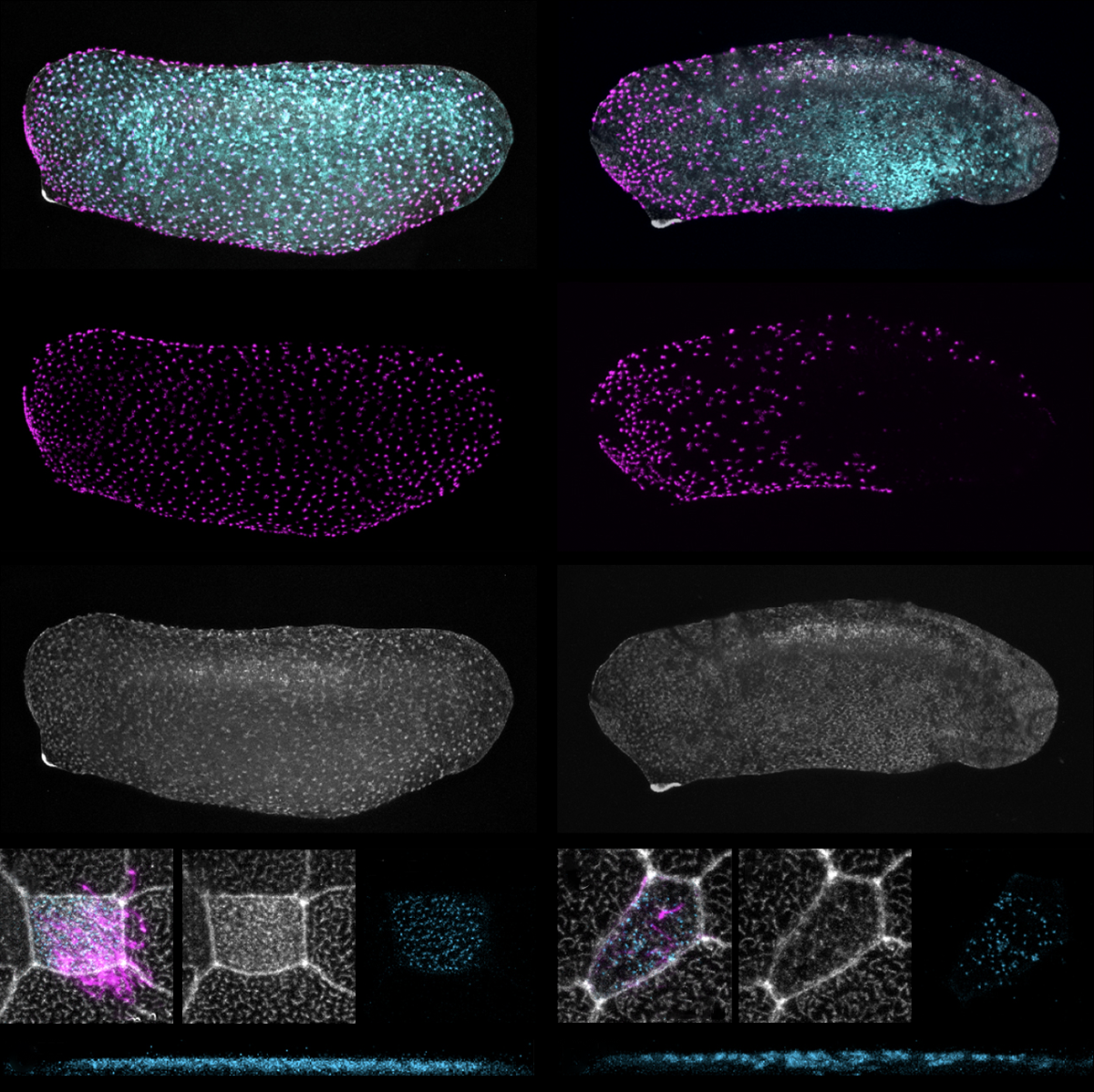

At least a dozen autism-related proteins localize to cilia, according to a preprint released in January. In the new work, the same team of researchers used CRISPR to introduce damaging variants into 104 genes associated with both autism and CHD in neural progenitor cells.

The variants introduced into seven of those genes severely affected the cells’ proliferation. These genes are likely to be involved in cilia, based on existing databases of gene function.

Finding those genes “was really exciting,” says Helen Willsey, assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of California, San Francisco, who co-led the new work. That “told us that we need to keep going, and that there may be more to this cilia connection than has been historically appreciated.”

Repressing each of the seven genes one at a time in retinal pigment epithelial cells significantly reduced the percentage of cells sporting cilia. For six of those genes, cilia were shorter than usual. The same thing happened in neural progenitor cells when the team suppressed TAOK1 and KMT2E, two high-confidence autism-linked genes that have not been directly shown to be involved in cilia.

Reducing the expression of TAOK1 in the embryos of Xenopus tropicalis, a species of frog, impaired cilia formation and the frogs developed smaller forebrains and hearts than usual.

T

he results show that TAOK1 is “certainly important for heart development,” says Bruce Gelb, dean of child health research at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mt. Sinai, who was not involved in the work. But a smaller heart isn’t necessarily the same as CHD, he says, and the team should follow up with work in mice to see if clearer CHD phenotypes emerge.Gelb co-led a 2015 study and another in 2017 that pointed to chromatin-modifying (or gene-expression regulating) genes as the intersection between autism and CHD. Chromatin regulators can also affect tubulin, the building block of microtubules, which are the central structure of cilia, according to a 2023 paper by Willsey’s team. In fact, the genes that Willsey’s January preprint linked to cilia are chromatin regulators.

“So, we think that there may be more to this chromatin regulation convergence than necessarily just gene expression changes, and that also may be a part of this cilia story,” she says.

A mystery remains: How do cilia disruptions contribute to autism?

“Ultimately, the critical question is whether changes in ciliary number and structure—and the resulting ciliary dysfunction—play a role in manifesting autistic-like features in model organisms,” Mustafa Sahin, professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School, wrote in an email to The Transmitter. Sahin was not involved in the new study but co-authored a 2022 review paper on the growing evidence for cilia defects in various neurodevelopmental disorders. “Unraveling this connection could be considered the ‘holy grail’ in cilia-related autism research,” he said.

Recommended reading

Sex bias in autism drops as age at diagnosis rises

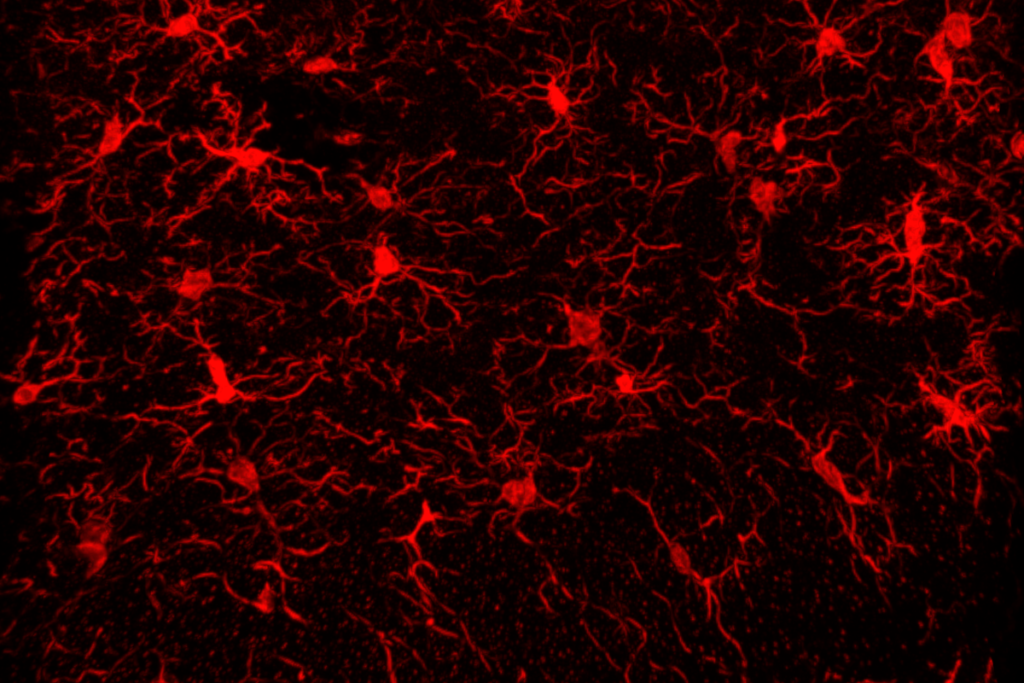

Microglia implicated in infantile amnesia

Explore more from The Transmitter

Anti-seizure medications in pregnancy; TBR1 gene; microglia

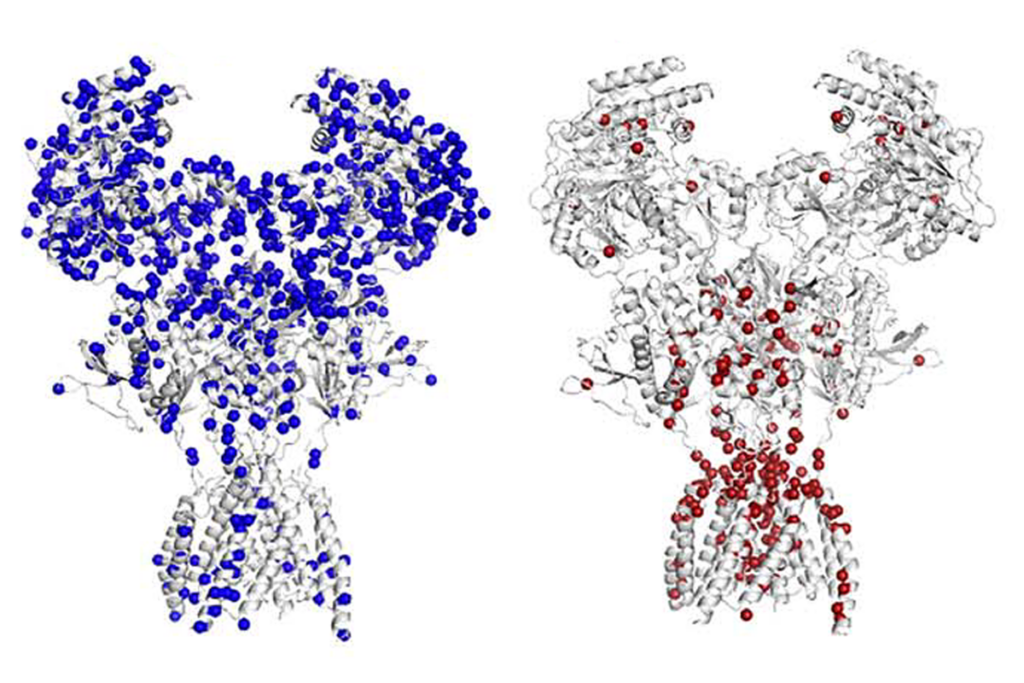

Emotional dysregulation; NMDA receptor variation; frank autism