Pregnant people who develop a severe infection show a slight increase in their chances of having an autistic child, according to multiple studies from the past two decades.

Still, many people become ill during pregnancy, and most do not go on to have a child with autism.

It’s not yet clear whether maternal infection actually contributes to a child’s autism or is just somehow more likely to occur among the mothers of autistic children. Here we explain what scientists know about the connection.

What evidence links autism to infection during pregnancy?

Following an outbreak of rubella in the United States in the mid-1960s, several epidemiologists reported an increased rate of autism among children whose mothers contracted the virus during pregnancy. Since then, numerous epidemiological studies have tied autism to maternal infection with influenza and other pathogens.

Being hospitalized with an infection during pregnancy may raise the chances of having an autistic child by 37 percent, according to a large 2014 study. Still, the overall increase in likelihood is still quite small — from 1 percent to 1.3 percent.

Many potentially confounding factors that are also linked to autism — such as a parent’s genetics or their nutrition, environmental exposures, age and weight during pregnancy — complicate the interpretation of the epidemiological findings, says Christopher Coe, professor emeritus of biopsychology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

But lab experiments lend support to the apparent link between prenatal infection and autism. For example, exposing pregnant mice to molecules from a common parasite activated a broad immune response, resulting in pups that showed autism-like behaviors and altered levels of immune cells, a 2021 study found. Exposure to compounds that mimic viruses or bacteria has yielded similar results in animal models.

Still, studies on lab animals “tend to use more severe infections or experimental manipulations that create large inflammatory reactions in the pregnant female,” Coe says. “Thus, they are more likely to have bigger effects on the fetus and ones that persist after birth in the developing infant.”

How might prenatal infections contribute to autism?

Infections induce high concentrations of molecules known as cytokines, such as interleukin-6 (IL-6) and IL-17, which can trigger inflammation and may influence fetal brain development, animal studies suggest.

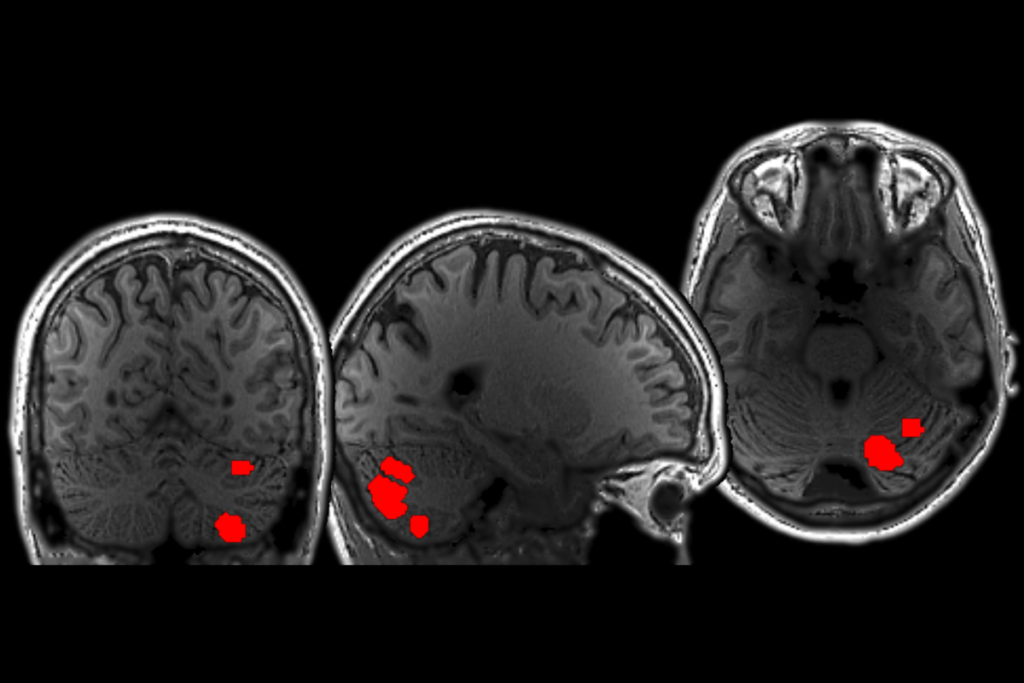

Inflammatory cytokines may work in combination with other genetic and environmental factors to increase the likelihood of autism and other neurodevelopmental conditions, says Melissa Bauman, professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the University of California, Davis. For example, genetic variants that are thought to boost levels of IL-6 are associated with differences in the volume or thickness of brain regions tied to autism, a 2022 study found.

A pregnant person’s antibodies may also alter fetal brain development. Maternal antibodies typically protect fetuses from infections but can sometimes mistake fetal proteins for foreign invaders. These so-called autoantibodies can cross the placenta to attach to developing neurons in fetal rats, resulting in some autism-like traits in the pups, such as repetitive behaviors and atypical socializing, studies suggest. About 10 percent of women with autistic children carry anti-brain autoantibodies in their blood, a 2013 study suggests.

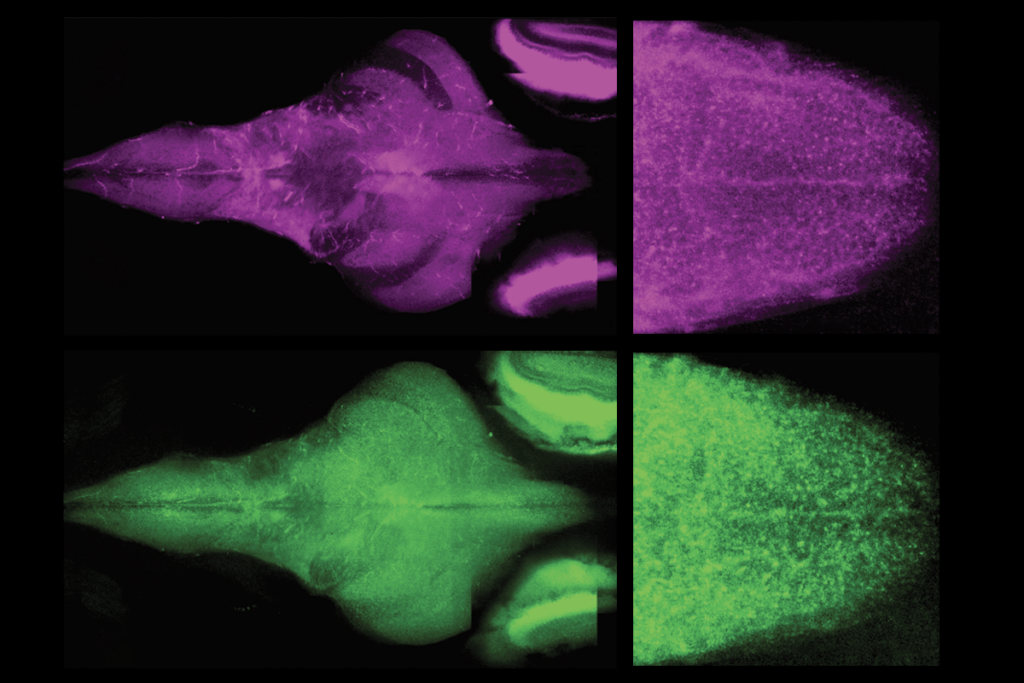

Prenatal exposure to infection may alter the activity of many genes linked to autism, triggering changes in brain anatomy, a 2019 study in mice discovered. That research found a chemical that mimics a flu infection decreased gene activity associated with the production of new brain cells while ramping up genes involved with neuron maturation.

And a pregnant mouse’s response to infection can alter the immune cells in its pups’ brains. These immune cells, or microglia, shape connections between neurons and may contribute to autism-like behaviors in the pups.

Besides potentially influencing brain development, what other effects might prenatal infections have?

Pregnant mice that launch immune reactions can have pups with not only autism-like traits but an increased susceptibility to gut inflammation. This finding may help explain why many autistic people have gastrointestinal issues.

What role might a pregnant person’s genetics play when it comes to this potential link?

It’s unclear. Genes that contribute to autism, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and schizophrenia may also contribute to prenatal factors that are associated with those conditions, according to a 2022 study of Norwegian families.

Alternatively, infection during pregnancy may be associated with having an autistic child simply because the mothers of autistic children are prone to infections, a 2022 study in Sweden found. This study, which focused on people who experienced prenatal infections severe enough to warrant specialized health care, suggests the strength of the link may be more modest than previously thought, says Charis Eng, chair of the Cleveland Clinic’s Genomic Medicine Institute in Ohio.

Do these new results erase the link between autism and infection?

No. The researchers behind the 2022 study in Sweden do not rule out the possibility that illnesses they did not analyze might contribute to autism — for example, relatively mild infections that didn’t call for specialized health care, or rare contagions. Women or children with a genetic predisposition to autism may also respond in different ways to prenatal infections than those without such propensities.

“We as humans tend to love simple, straightforward assessments of cause and effect,” says Brian Lee, associate professor of epidemiology and biostatistics at Drexel University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and an investigator on the 2022 study in Sweden. “For example, smoking causes lung cancer. However, that is clearly not the whole of it, as there are many smokers who do not end up getting lung cancer. In this same way, I don’t think our study disproves a maternal infection and autism spectrum disorder link. Rather, we show that familial genetics is somehow involved in the story.”

Does it matter when an infection occurs during pregnancy?

Experiments on animals suggest that the timing of infections can strongly influence the prenatal effects. “The finely orchestrated events of fetal brain development may have specific windows of vulnerability,” Bauman says.

Similarly, a 2016 meta-analysis of 15 studies found that an illness during the second or third trimester may boost the likelihood of autism by 13 to 14 percent. Infection during the first trimester didn’t appear to have a significant effect.

Does infection severity matter?

Maybe. Pregnant mice with middling immune reactions to infections tend to have pups with the most pronounced behavioral deficits, a 2020 study found. This raises the possibility that stronger immune responses confer resilience to psychiatric conditions through unknown mechanisms, Bauman says.

“We are still at the earliest stages of understanding the role that the intrauterine environment plays in shaping individual differences in brain and behavioral development, and what, if any, causal links there are to neurodevelopmental disorders,” Bauman says.

Could the COVID-19 pandemic contribute to a rise in autism prevalence?

Scientists are investigating this possibility. In the meantime, “if a woman of child-bearing age is planning to have a child, she should take advantage of the available, safe vaccines,” Coe says. If a person is concerned about taking COVID-19 vaccines while pregnant, “then get immunized before conceiving, although studies indicate that the Moderna and Pfizer vaccines are safe to take while pregnant.”

Although COVID-19 infection during pregnancy has not proven as deleterious to fetal brain development as initially feared, “if an unvaccinated woman becomes sick enough to require going into the ICU and needing to be on a ventilator, that is obviously not a good outcome for either her or her baby,” Coe says. Severe COVID-19 is associated with an increased risk of pregnancy complications such as preterm birth, which are in turn linked with a greater chance of a child having autism.

How concerned should parents be about the potential effects of infection during pregnancy?

The vast majority of pregnancies appear to resist the disruptive impacts of maternal infection and the subsequent immune response, Bauman says. “However, for a subset of women, exposure to infection does appear to increase the risk of altered fetal neurodevelopment,” she adds. “We need to better understand which pregnancies are most vulnerable, in order to provide evidence-based guidelines for managing infections during pregnancy.”

Ultimately, investigating any links between maternal infection and autism is important “because infection is modifiable,” Lee says. “If, and this is a very big if, we were able to identify specific infectious agents that resulted in adverse neurodevelopment — for example, maternal rubella infection or Zika — we might be able to intervene on that specific infection to reduce fetal risk.”